15 novembre 2018

Tendances du secteur

In recent years, there has been something of a revival of postmodernism, led by London-based textile, graphic and interior designer, Camille Walala, and even more recently, in architecture. According to designer Adam Nathaniel Freeman, the age of postmodern architecture is far from over.

Along with architect Terry Farrell, Furman recently published a book titled Revisiting Postmodernism, in which he argues that the movement is experiencing a resurgence, despite the backlash against it, one example being the characterful House for Essex created by FAT and Grayson Perry.

The Movement and Its Origins

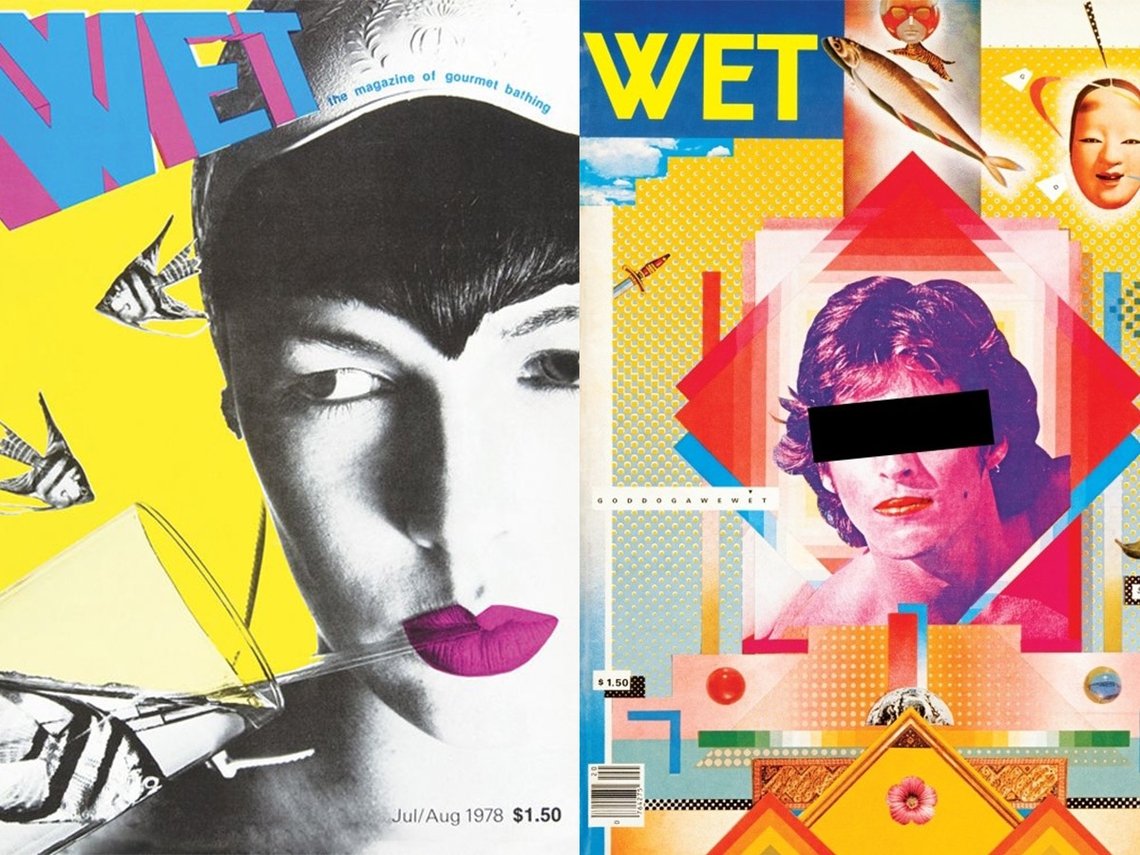

By the 1970s there was a reaction against modernism. A new wave of playful, iconoclastic postmodern designers reacted against its purity by offering an alternative vision for design that was warmer, more colourful, more experimental and more fun. While modernism had been based on principles of clarity and simplicity, postmodernism was about complexity, and contradiction. There were no boundaries anymore, and no more rules. From this point onwards designers could do whatever they wanted, and in the 1980s this newfound freedom in postmodernism design would come to dominate. While postmodern architecture was dominated by Americans, postmodern design was led by avant-garde Italians: such as Studio Alchimia, founded by Alessandro Guerriero in Milan in 1976, and particularly the Memphis Group, founded by Ettore Sottsass in that same city in 1981.

For the next four years, until Sottsass unexpectedly left the group in 1985, Northern Italians set the aesthetic tone in a way that had not been seen since the days of Renaissance Florence. Memphis furniture, as can be seen from the image of the room above, was made in unusual ornamental shapes and decorated with outlandish patterns and vivid colours. Every surface was covered in plastic laminate so that it shone. Compared to the monotone and the minimalism of so much modern design it was shocking – and it was supposed to be shocking. Sottsass and his cohorts were very self-aware and they loved theatricality and exaggeration. Everything was a style statement in their 1980s heyday. When Karl Lagerfeld was appointed head designer of Chanel in 1983, journalists arriving at his apartment in Monaco and were amazed to find it absolutely filled with Memphis furniture, including key pieces and also some prototypes that were never released. He had built a postmodern shrine for himself. In the middle of his living room, in place of a sofa, was a Memphis boxing ring scattered with a few cushions: Masanori Umeda’s Tawaraya Party Ring.

Throughout the 1980s the postmodernism design style came to take over popular culture, especially in the booming United States. The Memphis influence could be seen everywhere: from MTV, on which a postmodern design sensibility was apparent in the idents and the music videos it showed; to the diner where the high school kids hung out in Saved by the Bell; to the interior decoration of Taco Bell restaurants and Baskin-Robbins ice cream parlours. Postmodern design had conquered everything and, like the Roman Empire, this was to prove its downfall. It was no longer avant-garde, its leader Ettore Sottsass had left a long time ago, and by the early 1990s it was collapsing under the weight of its own ubiquity. Recently however there has been some form of revival, led by London designer Camille Walala who, as can be seen in the building mural above, finds much of her inspiration in the postmodern movement. Whether designing cladding or textiles, furnishings or ceramics, her bright patterns filled with dots and dashes bring us right back to the golden days of Memphis – but with a contemporary twist.

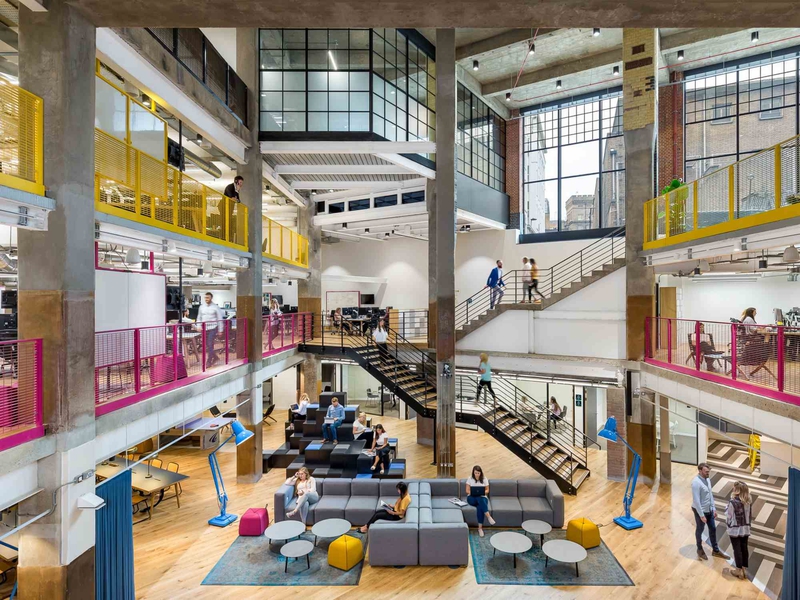

But as the 21st century progresses, although postmodernism is being revisited, design is becoming more and more focused on the user experience, and Spacestor continue to research and enhance this in the workspace environment. Having followed the changing trends over the years including London design and Californian heritage of modern, simple, democratic furniture from the 1950’s and 1960’s, it has informed much of our thinking here at Spacestor.

Partager cet article