The Way We're Wired - Designing for Neurodiversity with HOK & M Moser

How do we create spaces where every mind can thrive?

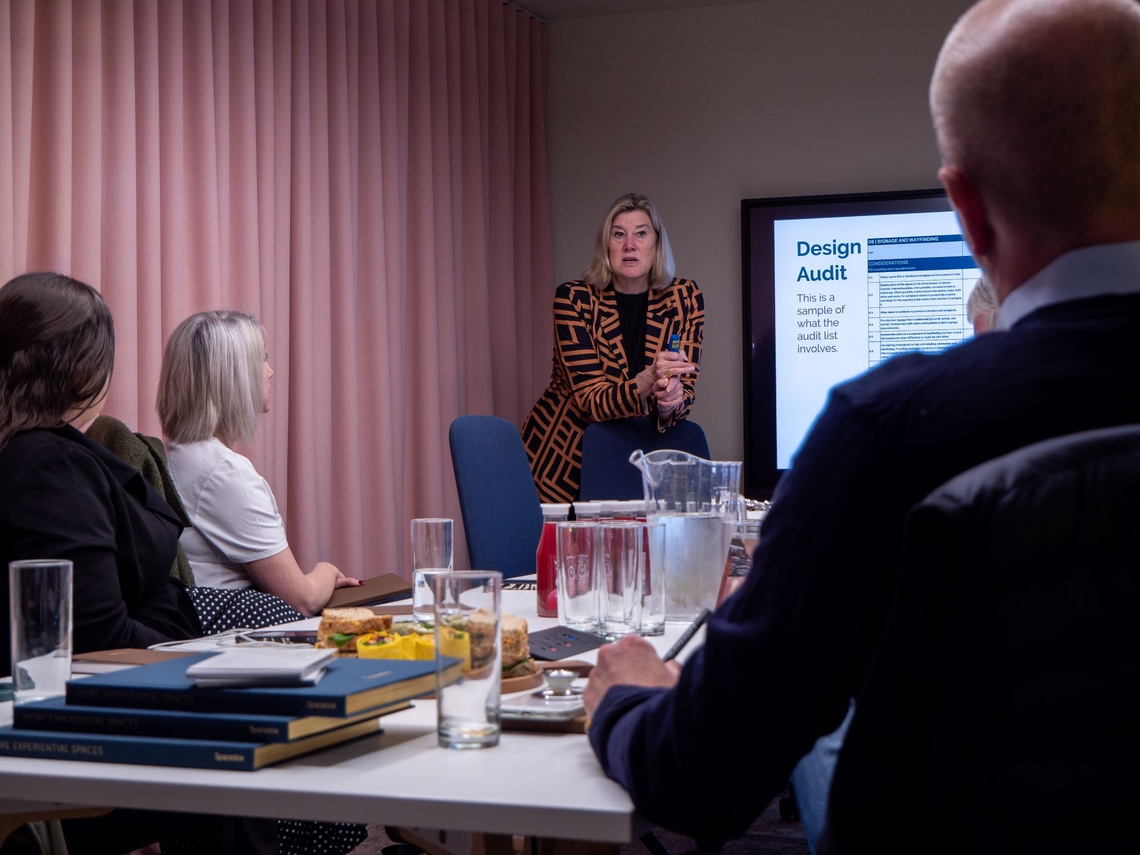

That was the central question explored at Spacestor’s recent roundtable event, hosted in our London Design Centre, with two respected voices on neuro-inclusive workplace design - Kay Sargent, HOK and Frances Gain, M Moser. Joined by a group of workplace professionals from large corporates, the session brought together fascinating insights, real challenges, and shared ambitions to push the design conversation beyond the average.

Read on for some of our highlights of the event!

“It’s not a deficit. It’s a difference.”

Kay Sargent kicked off the session with a powerful provocation: "We really look at this as a difference, not a deficit." As Director of Thought Leadership, Interiors at HOK, Kay has spent the past eight years digging into what it truly means to design workplaces that serve neurodiverse teams - and the landscape is shifting fast.

From one in eight to now one in five (and likely more) people identifying as neurodivergent, the urgency is clear. But the opportunity? Even more exciting. Designing for neurodiversity, Kay argued, isn’t about compliance or accommodation. It’s about performance, well-being, and creating environments where everyone - not just the outliers - can thrive.

Sensory Design Isn’t Optional

One of Kay’s standout observations was the idea that we’re all managing sensory overload - but for some, it’s not just uncomfortable, it’s debilitating. Whether it’s the buzz of fluorescent lights or the patterns on a floor, design details that seem small can have huge cognitive impacts.

“In fact,” Kay explained, “people that are neurodivergent might just be the canary in the coal mine. They feel it first, but it doesn’t mean everyone else isn’t affected.”

The solution? A shift from binary thinking toward providing both hyper- and hypo-sensitive spaces and recognising that different people need vastly different environments to do their best work.

“We’re pureeing the workplace”

Kay had the room laughing (and nodding) with an unforgettable metaphor about what’s gone wrong in workplace planning: "We’re pureeing it." Instead of clearly zoned spaces, many open offices are becoming over-blended – offering choice, but no true quiet, no true collaboration, just a muddled in-between.

“Imagine I made you a beautiful salmon sandwich, salad with burrata and tomatoes, and a brownie… then I threw it all in a blender and served it in a glass. That’s what we’re doing when we mix all work modes into one space.”

The takeaway? Clarity and zoning are key. Designers need to move past one-size-fits-all and embrace neighbourhood-based layouts with varied sensory zones concentrated on each need.

Frances Gain: “Difference is discovery”

Frances Gain, Strategy & Transformation EMEA at M Moser brought in the human element, sharing stories from her firm’s journey, which began with a personal diagnosis and led to a firm-wide shift in understanding neurodiversity not as a challenge, but as an opportunity for innovation.

At one client’s campus, she noted how neurodiverse employees organically created a self-organising network, recommending parts of the building to each other based on sensory preferences - daylight, quiet corners, calming views. “That was the beauty of it,” Frances explained. “It wasn’t top-down. It was natural.”

Frances also challenged the idea of designing for neurodivergent people as a static category. “It’s not a noun — it’s a verb. It’s something you do. You actively make a space inclusive.”

Design With, Not For

Across both talks, one core theme emerged: designing for neurodiversity isn’t a niche strategy - it’s a mainstream necessity. Not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because it makes good business sense.

Research shared by Kay from HOK showed up to 32% increases in access to quiet spaces, 16% boosts in productivity, and improved well-being when neuro-inclusive design principles were applied. In short: better environments benefit everyone.

So What’s Next?

This event wasn’t about presenting all the answers. It was about gathering the right people to ask better questions - and continuing the work of experimentation, sharing, and intentional design.

As Kay put it: “Once you learn how to design smart, it’s hard to go back to designing stupid.”

Every workplace is different, and so is every brain. But the more we tune in to what people really need - choice, control, calm, stimulation, a sense of belonging - the closer we get to building workplaces that work for everyone.